Written by B.D. Ingram

This post is still in a preliminary condition, edits may be made for correction of content and grammar.

Very few people today have heard of the USS Jacob Jones (DD-61), the first American destroyer lost to enemy action on a cold December day in 1917.

The American naval involvement in the First World War in general is little known today, despite the numbers of ships and men deployed. Fifteen American warships were sunk by direct enemy action, such as gunfire, torpedoes, and bombs. Many more were damaged and sunk by mines, and by simple accidents such as collisions with other ships. Hundreds of men lost their lives aboard those ships in 1917 and 1918, fighting for control of the North Atlantic and North Seas.

History

USS Jacob Jones was a destroyer in the Tucker class, the fourth of five classes of 1,000 ton destroyers ordered and built by the United States before its entry into WWI. At the time war was declared, they were the newest destroyers in service with the US Navy. There were twenty six 1,000 tonners in all, significantly larger than the 'Flivvers' that proceeded them, armed with fewer but larger guns, larger torpedoes, and much larger crews of nearly 100 officers and men.

The 1,000 tonners were also the first American warships to reach the other side of the Atlantic after the US entered the war. CDR Joseph K. Taussig's eight-strong Destroyer Division Eight reached Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland on the 4th of May, 1917. More destroyers soon followed, where they carried out anti-submarine patrols, search and rescue, and convoy escort.

DD-61's keel was laid on August 3rd, 1914 at the New York Shipbuilding Corporation in Camden, New Jersey. May 29th, 1915 was the date of her launch, and she was commissioned into the fleet on the 10th of February, 1916.

In March she steamed to Newport, Rhode Island for trials and exercises. Later that month she was sent south, to operate from Key West for shakedown and more trials, then she went to Tampa. There a crewman had to be quarantined due to smallpox, and his sleeping compartment was fumigated.

This pattern of exercises and trials continued into May, when she had her condensers repaired. Finishing up trials proved difficult, On the 19th of August, while operating out of Newport, a gasket on a main steam line ruptured while running a final trial.

October saw the German U-Boat U-53, under the command of Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, visit Newport. Jacob Jones noted the submarine's arrival and departure and was one of the seventeen destroyers that put to sea to rescue survivors of five merchant ships sunk by U-53 off Massachusets. U-53 would cross paths with Jacob Jones again later.

Trials continued to be difficult, with the engines causing issues into late January 1917, and prompting the navy to consider returning her to the builder. Then on the 5th of February, she collided with USS Beale (DD-40) while on her way to Philadelphia for more repairs. But by the 11th, her commander reported that the ship was ready for sea.

She made an excursion to Guantanamo Bay to escort the battleship New Hampshire (BB-25) north to Virginia, then went to Norfolk on the 23rd of March. The Atlantic Fleet was gathering there, and on April 6th the United States declared war on Germany. For most of the rest of April, Jacob Jones patrolled off the east coast, until new orders came for the ship to head to Boston to prepare for distant service.

Into Combat

Destroyer Division Seven, six ships in all, sailed from Boston on the 7th of May. Nine days out from Boston, a U-Boat fired a torpedo at the group, today its thought that Jacob Jones was the target. However the torpedo broached (came to the surface of the ocean) and went off-course, and the division arrived in Queenstown on the 17th without further incident.

The next day they began patrolling the western approaches, and Jacob Jones fired her first shots in anger on June 7th. She dropped depth charges on a large oil slick, which it was thought indicated a submerged submarine. However no positive confirmation of a kill was seen, the same result came of another attack on the 28th.

July 8th,

Jacob Jones was on escort duty west of Ireland when a large explosion appeared on the horizon, quickly followed by a distress call. The British steamer Valetta had been torpedoed by U-87. Jacob Jones and another destroyer, USS Perkins (DD-26) raced to the scene. 44 survivors of the torpedoed ship Valetta were rescued by Jacob Jones, but Perkins was unable to sink the attacking U-Boat. (U-87 would be sunk with all hands in the Irish Sea on December 25th, 1917 by the British patrol boat P 56). Shortly after on the same day the two destroyers went to assist the Cuthbert, but the steamer was able to evade the U-Boat.

July 15th,

Jacob Jones went to assist the steamer Abinsi late in the day. At about 2000 hours, while closing to hailing distance, the ships collided. Jacob Jones's whaleboat was destroyed in the collision, and ultimately no fault was attributed to either ship. The U-Boat that Abinsi reported was not engaged.

July 20th,

Jacob Jones engaged another U-Boat on the 20th, after spending the morning sinking a derelict ship and in target practice, at 1318 hours she spotted and closed on a U-Boat that was about six miles away. Two depth charges were dropped, but other than the oil slick they'd targeted there was no confirmation of a kill.

July 21st,

Escort work continued the next day, as the British steamer Dafila and the American steamer Dayton made their way through the western approaches in a moderate fog. A periscope was spotted 500 yards to the port and slightly astern of Jacob Jones, between the destroyer and Dafila.

U-45's torpedo hit home a few seconds later, smacking right amidships on Dafila's starboard side. The U-Boat was able to dive away before Jacob Jones could get shells on target, and another torpedo passed within 25 yards of the stern as the destroyer moved to engage the submarine. But it was able to escape, and Jacob Jones returned after 30 minutes of hunting to take survivors from Dafila aboard.

The submarine was not sunk or deterred though, and as Jacob Jones took the 25 survivors aboard a periscope was spotted again. This time the guns started to fire, and the destroyer accelerated in time to evade a second torpedo, again within 25 yards of the stern. Several more hours of hunting the submarine turned up no results, but Dayton was able to vacate the area safely. Dafila's survivors were turned over to a British ship the next day.

September 5th,

At 2230 a submarine was spotted 1,500 yards away, off the port bow. The #1 gun engaged but malfunctioned, and the submarine was able to submerge when Jacob Jones was about 400 yards away. Depth charges were dropped on a wake that they thought was from the U-Boat. Oil and even a body were reported after the explosion, but another hour of searching did not turn up any debris or other sign of a sunk submarine.

October 19th,

The Armed Merchant Cruiser HMS Orama was leading convoy H.D.7 from Dakar, which had departed on the 7th of October. A force of escorting destroyers joined up at 0225 hours, among them was Jacob Jones, along with USS Conyngham (DD-58), USS Nicholson (DD-52), and at least seven other destroyers.

At 0900 Nicholson departed to assist another merchant ship that was being shot at by a U-Boat, an American steamship named J. L. Luckenbach. One ship dropped out of the convoy with engine trouble along with another destroyer, and the convoy was joined by a ship. Reports of U-Boats ahead arrived in the early afternoon, but attempts to persuade the convoy to change course failed.

Conyngham was in communication with Orama again at 1755 hours, trying to get the convoy to change course to evade the U-Boats. To no avail, as U-62 was able to put a torpedo into the AMC's port side. Jacob Jones didn't participate in the hunt for U-62, and instead was ordered to assist Orama's crew.

Conyngham was able to engage the submarine, and dropped a depth charge on where it had dove away from periscope depth. Overall, 593 of the passengers and crew aboard Orama were rescued, with Jacob Jones recovering 305 survivors. Despite this exceptional effort, either four or five men perished from their injuries over the next weeks (sources vary).

U-62 (commanded by Kapitänleutnant Ernst Hashagen) survived the depth charging and would last until the end of the war. The survivors of Orama were disembarked the next day at Milford Haven in Wales.

November 17th,

While escorting convoy O.Q. 20, Jacob Jones was witness to one of the only confirmed American U-Boat kills of WWI. USS Fanning (DD-37) was able to drop a depth charge that doomed U-58, destroying motors, severing oil lines, and damaging diving gear.

Before an emergency ascent was started, U-58 had plunged to around 200 feet (Type U 57 U-Boats like U-58 had a normal maximum depth of only about 160 feet). USS Nicholson (DD-52) saw the conning tower break the surface, dropped another depth charge close to the crippled submarine, and opened fire with her 4'' guns. Fanning also joined in with her 3'' guns.

U-58 fully surfaced, and quickly the crew emerged from the hatches with their hands in the air. Two members of the crew perished, but the rest, including the commanding officer Kapitänleutnant Gustav Amberger were taken prisoner.

Fanning's victory over U-58 is the only confirmed solo American U-Boat kill of WWI, all others were in cooperation with the Royal Navy.

December 6th,

Underway to Queenstown after escorting a convoy to Brest, France, Jacob Jones engaged in target practice in the afternoon. U-53, still under the command of Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, heard the noise of the gunfire and closed in. Remaining undetected, a single torpedo was fired toward the destroyer.

At 1621 hours the incoming weapon was spotted, the deck officer Lt. (j.g.) Stanton Kalk ordered a hard turn to port, and LtCdr. Bagley rang up maximum power.

The torpedo struck the starboard side, hitting a fuel oil tank between some of the stern crew space and the auxiliary machinery room, about three feet below the waterline. One of the seven officers aboard, Lt. Harry R. Hood was standing above the point of impact and was killed instantly. An unknown number of other men were killed instantly by the explosion, many more were injured or rendered unconscious from being thrown around inside the ship, and the frigid ocean rapidly poured in through the hole.

This is the stern of USS Wilkes, DD-67, showing the arrangement of the fuel tanks between the stern crew spaces and machinery rooms. Jacob Jones should have a similar design, but lacked the 1-pounder antiaircraft gun.

Jacob Jones rapidly settled by the stern. In the engine room, Fireman First Class David R. Carter tried but was unable to secure the watertight hatch between the auxiliary room and the rest of the engine space.

Above, Coxwain Benjamin Nunnery was in the crew's washroom when the torpedo hit. He was one of the few of the roughly ten men in the compartment not seriously injured when they were thrown against the ceiling by the force of the blast. He made it to his gun station at the bow, and assisted in firing in the direction of the attacking U-53, in an effort to force the submarine to stay below.

Lt. Norman Scott worked in the machinery spaces to shut off steam going back to the engine room to prevent potential explosions.

Ll John Richards Jr., the gunnery officer, struggled to reach the stern to properly activate the safety systems on the depth charges stored there. But the damage was too serious, and Jacob Jones was sinking too quickly.

Efforts by LtCdr. Bagley to send an SOS also failed because the mainmast, and its attached antennas had been lost from the force of the explosion. Despite this, efforts were made to set up a power source from batteries normally used on the sights for the guns, and men saw radio operators with their headsets still on trying to send distress signals as the rest of the crew abandoned ship.

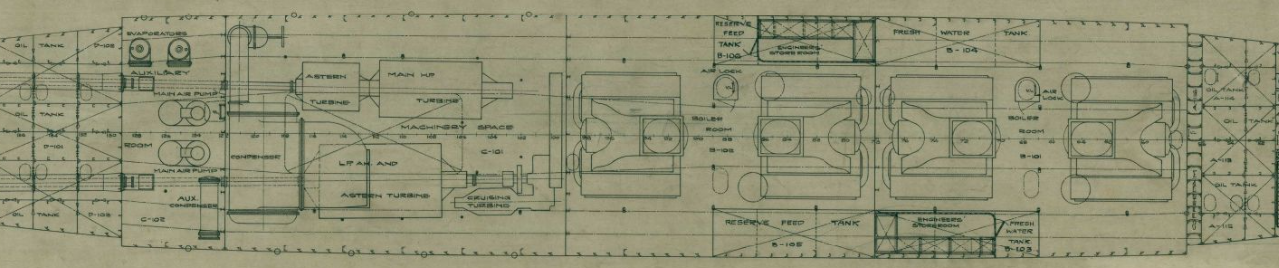

From the general plans of USS Wilkes, showing the approximate arrangement of the washroom where Coxwain Benjamin Nunnery was when the torpedo hit, and the location of the radio room.

CEM Lawrence Kelly was later credited with saving several lives for his efforts of freeing as much lifesaving equipment as possible from the ship before she sank.

Despite the heroic efforts of the crew, Jacob Jones was doomed, and LtCdr. Bagely ordered the crew to abandon ship.

Seaman 2nd Class Philip Burger remained with Jacob Jones until he was sucked underwater, trying to release the steam launch. He was able to make it back to the surface and survived. The Number 4 gun (the sternmost) was able to fire off two more shots in an attempt to attract any ships to come to the aid of the men now in boats or clinging to debris.

At 1629 hours, Jacob Jones's bow rose, twisted through 180 degrees, and then hung nearly vertical for a moment. Then the destroyer plunged stern-first into the deep.

The air temperature in December was just above freezing, and the water was also lethally cold.

But for the survivors things would get worse. The unsecured depth charges started to explode as the destroyer slipped deeper, killing and injuring many of the men who were in the water. The ship's motor dory, wherry (which was leaking), at least one other boat, a few rafts, and assorted debris were all the crew had to hold onto in the winter ocean.

Lt. Richards was physically thrown out of the water by the force of the blasts. Also among those injured was LtCdr. Bagely, he was pulled unconscious into the motor dorry after being bumped into by a crewman in the water.

Twenty two men were crammed onto one of the balsa rafts, eight more were on the Carley float (a common type of life raft until after the Second World War) that was lashed to it, with many more men clinging to the sides.

Lt. (j.g.) Kalk had also been wounded by the depth charges, but despite that on realizing that the raft he was aboard was dangerously overloaded, he swam over to the balsa raft to balance the loads.

U-53 surfaced at 1645 hours, and took two survivors (Seaman Second Class Albert De Mello and Seaman First Class John F. Murphy) of Jacob Jones's crew aboard before submerging again. Rose told the men that the wireless operator about U-53 was sending a radio message to alert the allies to the sinking, but that there wasn't enough room abord to take more men out of the water.

Despite this, the allies either didn't receive the message, or didn't act on it. Help would not come for several more hours. U-53 returned to Germany on the 12th of December, De Mello and Murphy survived their time as prisoners of war and returned to the United States after the armistice.

Overnight the weather got worse, with the wind increasing and causing serious waves that threatened to sink the boats and kept the survivors drenched and freezing cold. Men started to succumb to exhaustion and the elements.

Lt. (j.g.) Kalk succumbed to hypothermia around 2300, said to have been "game to the last." Cabin steward Wallace Simpson, an African-American sailor with a decade of time in the navy, was washed overboard from the Carley float he was aboard and drowned. Lt. Richards led the men in his Carley float in songs to keep them awake, alert, and to keep morale up.

“Survivors Awaiting Rescue Off the Isles of Scilly”, by F. Luis Mora; 1920

Most of the men were lightly dressed due to how quickly their ship was lost, and many men gave items of their own clothing to others who were lacking.

The first men rescued were picked up by the British merchantman Catalina, which came across a Carley float around 2100. It was a message from Catalina that mobilized the allies to start search and rescue operations, and several ships were dispatched from Ireland.

HMS Camellia, an Azalea class minesweeping sloop located the balsa raft and the Carley float that was lashed to it at 0900 on the 7th of December. Half an hour later another group of men on another float 600 yards away were rescued.

Despite valiant efforts, there had been no wireless message sent from Jacob Jones before she sank. So LtCdr. Bagley, Lt. Scott, and four of the strongest remaining men set out in the motor dory towards the Scilly Islands to seek assistance late on the 6th. They took turns rowing and bailing out the small craft, as its motor was inoperable and the sea was increasingly rough. Coxwain Nunnery was one of the men aboard, and he called the twenty two hour ordeal until they were rescued the most strenuous hours of his life.

They were rescued by a British patrol boat at 1300 hours a mere fifteen miles south of the Isles of Scilly, the last survivors of Jacob Jones to have been located. The wherry, with five men aboard, also had set towards the Scilly Islands. However, neither the boat nor the men aboard it, were ever seen again.

There were 110 officers and men aboard Jacob Jones on the morning of December 6th, between 63 and 66 officers and men were lost directly due to the torpedo impact or the night in the freezing ocean. Sources vary on the exact number of men who perished, and the number of survivors.

In Lieutenant Commander David W. Bagley’s own report on the sinking, he reports two officers and sixty four men lost with the ship. However, only 63 men and two officers were listed in the detailed list attached to that report. Further complicating matters is that two of the men he reported as probably lost were actually the men recovered by U-53.

Survivors from USS Jacob Jones. Of note is the man with the rank of Lieutenant second from the right, seated, and beside him a man who appears to be a Lieutenant (junior grade). Seven officers were said to be aboard Jacob Jones, of whom two died in the sinking and aftermath. However, it is unclear which officers this may be in the photograph as of the seven, two names seem to be absent from sources. It is possible that these men are Lt. John Richards Jr. and Lt. (j.g.) Nelson Gates, as Lt. (j.g.) Stanton Kalk perished on the night of the 6th, Lt. Harry Hood was killed when the torpedo struck, and LtCdr. David Bagley and Lt. Norman Scott were on the motor dory heading for the Scillies. Any further information would be appreciated.

These survivors were fed and treated by the British before they were disembarked at several different bases, in time they made their way to USS Melville (AD-2) in Queenstown. This was VADM Sims's flagship for American naval forces in Europe until 1919. They were then sent back to the US for recuperation and the majority of the survivors returned to the war in 1918.

Lessons were learned from this loss, VADM Sims issued guidelines regarding how boats and lifesaving equipment should be stored, and that destroyers should operate in pairs, always within visual range of each other. Also handling procedures for depth charges were changed as well, with them always kept in a safe condition.

Ten men received written commendations, four Navy Crosses were awarded, and the then-highest navy medal, the Distinguished Service Medal, was awarded to LtCdr. Bagley, Lt. (j.g.) Kalk, and Seaman Second Class Burger.

LtCdr. David Bagley had a very successful career through World War Two, serving as a naval attache in Europe, doing a tour in the Office of Naval Intelligence, commanded several more ships, commanded a series of training stations, became assistant bureau chief of the Bureau of Navigation, commanded a squadron of destroyers in 1936, and was promoted to admiral in 1938.

When World War Two broke out Rear Admiral Bagley was commander of Battleship Division 2 in Pearl Harbor, with his flagship being USS Tennessee (BB-43). In 1942 he took command of the Hawaiian Sea Frontier (a now disused term for in effect coastal defense regions) and the 14th Naval District. He moved to the Western Sea Frontier (the coast of the United States) in 1943, and was promoted to Vice Admiral in 1944. It seems he never commanded another ship, and was relieved of all duty in 1946, and was placed on the retired list in 1947. He was married and had three sons, all of whom served in the military. He passed away on May 24th, 1960.

There were four ships named Bagley, the first three were named for David Bagley's brother, Ensign Worth Bagley, who was killed in the Spanish American War (the only American naval officer killed in action in that war). The fourth USS Bagley (FF-1069, a Knox class frigate) was named for both brothers.

Rear Admiral Norman Scott, photo taken circa 1942.

Lt. Norman Scott is better known today for his actions in the Second World War, where he was killed in action aboard USS Atlanta by friendly fire from USS San Fransisco in the hellish nighttime fighting of the First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. He had a successful career in the 1920s and 30s, serving aboard battleships, destroyers, cruisers, and in a handful of ashore postings. In May 1942 he was promoted to Rear Admiral and commanded surface units in the invasion of Guadalcanal and Tulagi in August. He was a very combat-oriented commanded, and his night fighting training paid off at the Battle of Cape Esperance, where the task force he commanded smashed a Japanese one in a nighttime engagement.But he was second in command at the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, being a few days junior to Rear Admiral Danial J. Callaghan. Both admirals were killed in the action, and both were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. Two ships, USS Norman Scott (DD-690) and USS Scott (DDG-995) were named in his honor, as are several land based facilities.

Midshipman Stanton F. Kalk, photograph circa 1916, when he graduated the US Naval Academy.

Two destroyers were named for Kalk, DD-170 (Wickes class, laid down as USS Rogers, renamed on December 23rd, 1918. Served in the USN, RN, RCN, lost under tow in July 1945 on the way to Baltimore for scrapping), and DD-611 (Benson class, laid down 1941, served in the USN during the Second World War, received eight battle stars, decommissioned in 1946, sunk as a target in 1969.)

Two more ships would be named Jacob Jones, the first was a new Wickes class destroyer (DD-130) laid down in February 1918, mere months after the first had been sunk. She was decommissioned in 1922, but was reactivated in 1930 and carried out neutrality patrols and exercises for the rest of that decade. When the Second World War began she escorted ships in the Atlantic and hunted U-Boats. On the morning of February 28th, 1942, U-578 fired a spread of torpedoes at Jacob Jones. At least two, possibly three hit.

The results were immediate and catastrophic, of the crew only 25 to 30 officers and men survived the initial impacts and secondary explosions. History repeated itself, as the depth charges on the stern once again detonated when they reached their set depths, killing many more of those who survived. The handful of survivors were located and rescued later that morning, but one died before they reached the shore. Only eleven men of a crew of over a hundred lived to tell about what had happened.

The third, and last, USS Jacob Jones was DE-130, an Edsall class destroyer escort. She was laid down in June 1942, commissioned in April 1943, crossed the Atlantic twenty times as an escort ship, transited the Panama Canal to the Pacific after Germany surrendered, and was decommissioned in 1946. She was sold for scrap in 1973.

Technical Details

Jacob Jones was 315 feet and 3 inches long, at her widest point she was 29 feet and 11 inches, and she had a maximum draft of 10 feet and 5 inches. Normal displacement was 1,050 long tons, her maximum trial speed was 29.568 knots, as designed the complement was 6 officers and 95 men.

Unfortunately, plans for the Tucker class don't seem to be available online via the National Archives, so visuals will be of plans of other 1,000 tonners which are available. Particular specs for Jacob Jones also aren't available, so when needed other ships in the class will be referenced.

Engines

Oil firing was fairly new in the navy at the time, the oil-fired Paulding class of destroyers had only been authorized by Congress in 1909 (though in the late 1890s the Navy had experimented with oil firing aboard the USS Stiletto without much success). Oil has several advantages over coal, it has a significantly greater energy density so less needs to be carried for the same total power output, it's much easier and cleaner to load aboard ships, and it's easier to store in smaller spaces inside the hull, and oil boilers don't require nearly as many crewmen.

At normal loading, Jacob Jones had 206.1 long tons of fuel oil, at full she had 309.2 long tons. While the characteristics from the navy specified a range of 2,500 nm at 20 knots for the Tucker class, it's not clear what the exact range this provided actually was. Jacob Jones had accommodations for efficient cruising (more information below), there is a great deal of variation in the steaming range of ships in this period. Even among ships of the same class, with notionally identical powerplants.

"The report of the Commander, Torpedo Flotilla, Atlantic Fleet, showed for the DD 22-36 group a radius at economical speed varying from 2,424 nm. (the Perkins) to 3,919 nm. (the Patterson), and at 20 knots from 1,470 to 2,668 nm. in the same two ships."

-U.S. Destroyers

There were four Yarrow boilers aboard Jacob Jones, Yarrow boilers have a distinct triangular three-drum design and were very common aboard warships in the period (they have been seen on a few wrecks covered on this blog in the past). Most of the following description is derived from information about the boilers on USS Texas, a preserved museum ship, which has been well documented. Any suggestions or corrections from those with more direct access to information about steam powerplants aboard destroyers would be appreciated.

The top drum in a Yarrow Boiler is the steam drum (item A in the diagram below), the two lower drums (item B) are for water and are connected to the steam drum by a large number of tubes (item C). The firebox (item D) with the burners (in the case of oil-fired ships) is located directly below the steam drum between the array of tubes. As the water in the innermost tubes is heated it starts to rise, convection causes cooler water to be pulled down the outer tubes to ensure the water drums are always filled. Eventually, the water in the inside tubes boils, creating steam under high pressure, this pressure forces the steam out of the top of the steam drum to go do work elsewhere in the ship.

But the exact design details of these boilers are never that simple, as there are several features that are required for the safe and reliable operation of this type of boiler.

First was trying to get Dry Steam, that being pure steam, just water in its gaseous state without any particulates, water droplets, or other debris in it. This is important because naval boilers operate at very high pressures, which will accelerate any contaminants along the length of steam pipes like bullets, damaging anything that gets in their way. (Ships with expansion engines instead of turbines need a little bit of wetness in the steam though to lubricate the pistons, oil cannot be used because it would contaminate the water and cause several problems elsewhere in the system).

At the very top of the steam drum there's a pipe, with hundreds of small holes in the top, called the dry pipe (item 1). This is where the generated steam enters the system, the holes being up on top prevent droplets of water from getting into the system that way.

The makeup water line (item 2) is capped, to prevent makeup water from splashing up into the upper parts of the boiler, again to prevent water droplets from getting into the steam lines.

There is a grate (item 3) in the bottom of the steam drum, which covers the innermost tubes from the water drums, where the water is being boiled and turning into steam. Again, the grate prevents bubbles from causing splashing up into the upper parts of the steam drum.

There is a window into the steam drum so the water levels can be monitored, if it gets too low, the intense heat from the firebox will damage the boiler tubes, if it gets too high water will get into the dry pipe and cause damage elsewhere in the steam system.

Nineteen confirmed Water Tenders and Firemen aboard Jacob Jones perished in the sinking.

The steam went back to run the turbines, of which there were a few types for different types of steaming. There were the main ahead turbines, which were the largest and were directly attached to the propeller shafts. Each shaft also had an astern turbine for when the ship needed to go in reverse, these were smaller. Also, there was another smaller turbine attached to only one shaft for cruising.

Turbines are most efficient at very high RPMs, while propellers are more efficient at lower RPMs, also at lower speeds, they don't cavitate as much which reduces vibration and wear on the propeller. Older destroyers had a secondary expansion engine for cruising, and later destroyers had gearing systems to step down the speed of rotation between the turbines and the shafts.

At the back of the main turbine compartment was the condenser, which took the steam that had gone through the turbines and as the name implies, condensed it back down to water which was then piped back to the feed water tanks to go through the boilers again.

Other equipment of note in the ship's plans are the evaporators, these are distilling units to produce fresh water from seawater aboard the ship. It's possible that these provided fresh water for the crew, but the primary function of having evaporators like that aboard was to replenish the feed water for the boilers. While regular seawater can be used in steam powerplants, it rapidly causes issues with a buildup of scale and as a result, injects debris into the system.

Armament

Jacob Jones was armed like the other 1,000 tonners, with four 4''/50 guns in single mounts (one on the raised forecastle, one on each beam just aft of the forecastle, one on the stern), and eight 21'' torpedo tubes in four twin mounts, two mounts to each beam.

4''/50 Mark 9

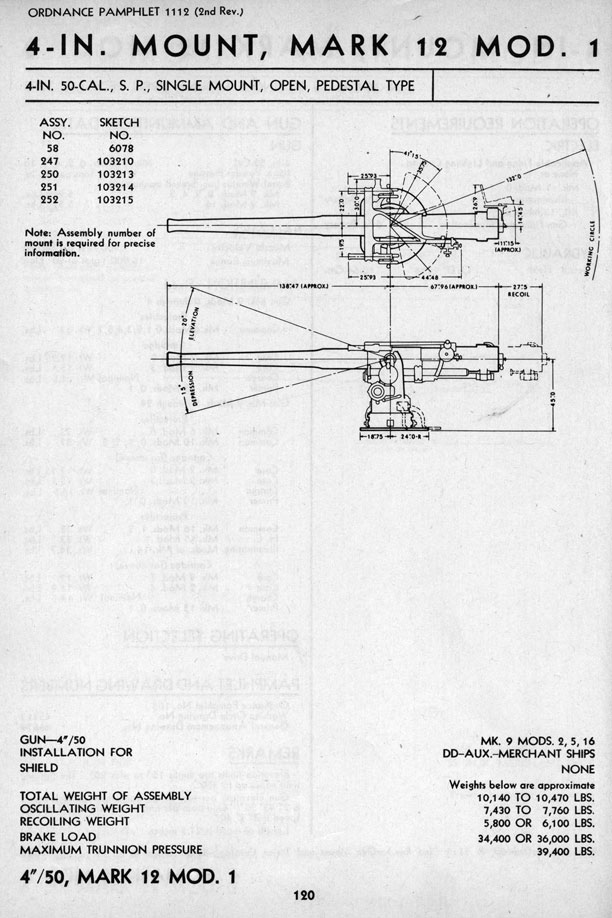

Drawing of a 4''/50 gun, from Gun Mount And Turret Catalog, Ordnance Pamphlet 1112, 1945. Via maritime.org

The 4''/50 was first fielded as a secondary gun on the Arkansas class monitors, and in 1913 became the main gun for the 1,000 tonners with the launch of USS Cassin (DD-43). It packed significantly more punch than the 3''/50 guns on the previous classes of destroyers, while also being light enough for fairly quick handling.

Finding the exact information about the guns and ammunition as they were in WWI is a bit difficult due to the very long service life of the system. The 4''/50 went from Mark 7 to Mark 10 over more than 40 years of US Naval service, from the late 1890s on the Arkansas class, all the way to the end of WWII and beyond aboard submarines, lend-lease destroyers, patrol craft, and Liberty ships among other types.

Alone, a gun weighed 2.725 tons, the gun plus the Mark 12 SP mount was 4.53 - 5.63 tons. Maximum elevation was 20 degrees up and 15 degrees down, and elevation and train were only manually operated.

Elevated to 20 degrees, a 33 pound armor-piercing shell with a muzzle velocity of 2,900 feet/second would travel 15,920 yards.

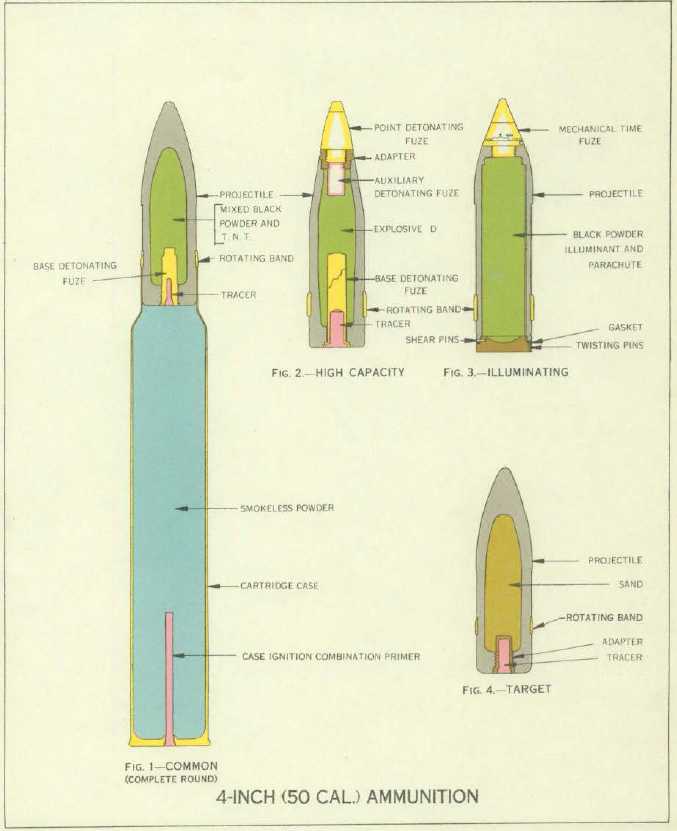

Ammunition was fixed, and a complete round weighed between 62.4 and 64.75 pounds, depending on the exact weight of the projectile, propellant, and case. Several types of projectiles were available and produced over the years.

Common shells, depending on the period, were filled with 1.1 pounds of black powder or 1.39 pounds of black powder and TNT. At least by WWII they also had a tracer compound in the base to allow the trajectory of the shell to be easily observed.

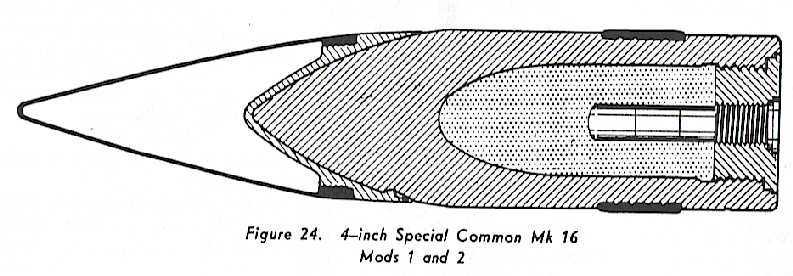

Cutaway drawing of a Special Common shell, from NavWeaps.com

After WWI there was a special purpose common shell which had a windshield (also known as a ballistic cap) and hood, which improved their ballistic performance. This also gave them some slightly better armor penetration capability. WWII figures listed for AP shells (probably some type of special common shell), list a maximum penetration of 3'' of vertical armor at 3,700 yards. It's not clear against what sort of armor this would be, but it would be very threatening to things such as submarines which while not armored, did have strongly built hulls to survive the pressures of undersea operation.

Illumination shells, also known as star shells, by WWII were filled with a sort of black powder illuminant and had a parachute to slow their descent.

Scale model of USS Sampson DD-63, showing the positioning of the guns and the shape of the forecastle to accommodate them.The guns on the main deck were positioned so that they could fire directly forward along the sides of the forecastle deck, but this made them difficult to operate in anything other than calm seas. Based on design drawings, the numbering of the guns went #1 being the one on the forecastle, #2 being on the main deck port side, #3 on the main deck starboard side, #4 main deck astern.

There were two magazine spaces, one in the bow and one in the stern, on the hold deck. Most destroyers carried about 300 rounds per gun, for a total of about 1,200 4'' shells overall.

Torpedoes

Previous destroyers had used torpedoes with an 18'' diameter, but the increased protection of warships against torpedo warheads, and the increasing effectiveness of anti-torpedo boat guns caused constant developments of larger and more powerful weapons.

The Bliss-Leavitt Mark 8 was the first American 21'' torpedo, and entered service in 1915. The early versions weighed 2,761 pounds, were 248 inches long, and had a warhead of 321 pounds of TNT. The Mark 8 would grow over the years, getting longer, heavier, and with a larger warhead.

It was powered by a wet heater turbine engine, where air, fuel, and water were all fed into a combustion chamber which reduced the temperature of the combustion and added a volume of steam to the gas going back to the actual engine. For this reason, these are often referred to as steam torpedoes, though there isn't actually much steam produced. The early versions of the Mark 8 had a range of 10,000 or 12,500 yards at a speed of 27 knots.

Diagram of the steam turbine and wet heater engine in Bliss-Leavitt torpedoes, image from A Brief History of U.S. Navy Torpedo Development, via maritime.org

Depth Charges

She also carried depth charges, based on the time of her sinking, the few photos there are of her in wartime service, and the circumstances of her sinking, the type of charges can probably be determined. Given the situation Jacob Jones was in, where she was based, and when in the war it was, she probably was carrying USN Mark II or a British-designed Type D depth charges.

The US Navy's Mark II depth charge was a derivative of the British Type D charge, first fielded in January 1916. These charges had an overall weight of 420 pounds, carried 300 pounds of explosives, and used a hydrostatic pistol to trigger the detonation.

A hydrostatic pistol is a pressure sensor, when it reaches a set depth the pressure fires the pistol which detonates the rest of the depth charge. In the Type D the settings were either 40 feet or 80 feet, the American Mark II had an improved fuze that allowed settings from 50 to 200 feet via an external dial.

In December 1917 the US Navy agreed to produce 15,000 Type Ds for the Royal Navy, though in US service the fuze was considered to be unreliable since it tended to explode prematurely when fired from a depth charge projector.

Due to production shortages, most ships only carried a handful of depth charges. But it's not clear from any accounts how many charges were aboard Jacob Jones at the time of her sinking. From the photographs available of the ship, and the wreck, it doesn't look like she had the more commonly thought of style of stern wracks where charges could just be rolled over the stern (though those were designed during WWI). However, it's possible there was another type of depth charge aboard at the time.

Sailor adjusting the depth setting of a Mark I depth charge, and in ready stance to throw it. Photo sourced from navweps.com.

The US Navy's Mark 1 depth charge was a somewhat simple weapon, weighing a mere 100 pounds, with a 50 pound explosive charge. There was no particular fixture or launch system, the strongest man on the crew was generally assigned to physically throw them over the side when a target was in the correct position.

The charge was in two sections and one would float while the other would sink, they were connected by a cable which unreeled as the warhead section sank. When the cable went taught at the set depth, it would explode. This could be set from 25 to 100 feet. But there were problems with reliability, and the explosive charge was too small to be very effective against a U-Boat. Ten thousand were ordered, but the Mark 1 didn't last very long in actual service.

Other Weapons

The forward magazine space on USS Wilkes, showing where the small arms were stored.

Tucker class destroyers did not have any other permanently mounted weapons, but there was a locker for storing small arms and ammunition for them. These would include pistols, line throwing guns, and probably a small assortment of rifles. Based on photographs of the 1914 occupation of Vera Cruz, ship's companies would have M1903 Springfield rifles, and most photographs that contain pistols show M1911s. It's possible that there were other weapons, as ships did sometimes deploy sailors as infantry or for general security, such as M1895 'potato digger' machine guns or 3''/21 field guns, but on a ship the size of Jacob Jones that is unlikely.

Other Equipment

Based on the plans for other ships of similar classes, there were probably four proper boats aboard the Jacob Jones in addition to the Carley floats and a few other rafts.

Cross sectional diagram of a Carley Float, author's own work.

The Carley float is a common sight in photographs of warships during the Second World War, but they were patented much earlier. These were constructed of steel or copper tubing filled with air and sealed, covered by a buoyant cork shell, and then with a waterproofed canvas cover. In the center of it all was a wooden grid that would make up the floor, regardless of which way the raft ended up in the water.

The photo below shows a Carley float on HMS Widgeon during WWII, it contains paddles and survival equipment lashed to the floor grid. The ropes around the sides are for more men to hold onto the raft than could normally fit inside it.

Other boats would be the 24 foot long motor sailing launch, the 21 foot motor dory, a 34 foot whaleboat, a 14 foot wherry, and based on other ships, there would have been a 10 foot punt as well.

Two of these had engines, the rest were propelled by sails or by oars.

The Wreck

The discovery of the wreck was announced on August 2022, by Steve Mortimer on Facebook. According to the post, Jacob Jones lies in 120 meters of water, 60 miles south of Newlyn, Cornwall.

This photo of the ship's bell was the first image released, and over the next several days, more photographs and video was released.

The boiler tubes of one of the four Yarrow boilers can be seen in this shot, it's not clear which though.

In the second screenshot, the supporting strut that held the end of the shaft to the rest of the ship can be seen, and the blades of the screw are illuminated.

Sources:

The Wreck

https://www.facebook.com/100001761500105/posts/pfbid0pBh7Tw2FanPffSe8MUXGxn8PUfdBjZhEDVFqgjEPpmcCmC8zZfbu25sVg5Mduxahl/?d=n - Original Facebook post announcement of the discovery.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EjboFAUCZ4s - BSAC divers help discover missing wreck of USS Jacob Jones 115m deep. Video of the survey of the wreck site.

General WWI US Naval History

https://destroyerhistory.org/early/operations/ - Overview of USN WWI destroyer operations.

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/a/american-ship-casualties-world-war.html - List of American ships damaged or sunk during WWI.

https://www.naval-history.net/WW1NavyUS-Ranks.htm - Officer Ranks and Enlisted Rates of the United States Navy during WWI.

Jacob Jones History

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/j/jacob-jones-i.html - Detailed ship's history of USS Jacob Jones.

http://www.navsource.org/archives/05/061.htm - Photographs of USS Jacob Jones.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/december-1917/lieutenant-commander-2.html - Lieutenant Commander David W. Bagley’s Report On Sinking Of U.S.S. Jacob Jones.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/december-1917/lieutenant-commander-1.html - Lieutenant Commander David W. Bagley's report on the sinking of USS Jacob Jones, includes a list of men known or thought to have been lost with the ship.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/december-1917/lieutenant-commander-1.html - Lieutenant Commander David W. Bagley, Commander, U.S.S. Jacob Jones, To Vice Admiral William S. Sims, Commander, United States Navy Forces Operating In European Waters.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-i/history/the-sinking-of-jacob-jones.html - The Sinking of Jacob Jones: Toughness and Sacrifice in the North Atlantic, Chester, S. Matthew, NHHC Histories and Archives Division, November 2017.

https://www.naval-history.net/WW1NavyUS-CasualtiesChrono1917-12Dec.htm#jacob%20jones - A list of the men lost aboard USS Jacob Jones, sixty three officers and men are listed.

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/research-guides/modern-biographical-files-ndl/modern-bios-b/bagley-david-w.html - Biography of David W. Bagley.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/research-guides/modern-biographical-files-ndl/modern-bios-s/scott-norman.html - Biography of Norman Scott.

https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-people/k/kalk-stanton-f.html - Biography of Stanton F. Kalk.

https://grandeguerre.icrc.org/en/File/Details/4179990/2/2/ - Red Cross information about Albert De Mello.

https://grandeguerre.icrc.org/en/File/Details/2143190/2/2/ - Red Cross information about John Murphy.

https://catalog.archives.gov/search?q=*:*&f.parentNaId=53490263&f.level=item&sort=naIdSort%20asc - General Plans for USS Wilkes, DD-67.

Weapons

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_4-50_mk9.php - 4''/50 Marks 7, 8, 9, and 10

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WTUS_PreWWII.php - Pre-WWII USN Torpedoes

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WAMBR_ASW.php - British ASW Weapons of WWI and later.

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WAMUS_ASW.php - American ASW Weapons of WWI and later.

British and German Officers, Men, and Ships

https://uboat.net/wwi/ships_hit/largest.html - Ships over 10,000 tons hit by U-boats during WWI.

https://uboat.net/wwi/boats/?boat=53 - Information about U-53.

https://uboat.net/wwi/men/commanders/273.html - Information about Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose.

https://www.uboat.net/wwi/boats/?boat=87 - Information about U-87.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment